Potatoes came from South America. According to archaeological and botanical studies, people started growing and domesticating potatoes at least 7,000 to 10,000 years ago. Spanish explorers brought potatoes from South America to Europe in the 1500s. Potatoes are now the fourth most important food crop in the world, after rice, wheat, and corn. There are many different shapes, colors, sizes, and textures of potatoes.

Unlike many other vegetables that are grown from seeds, potatoes are planted using seed potatoes. This is mainly due to their biological characteristics and production requirements. Potatoes reproduce vegetatively, and the buds (eyes) on the tubers are complete growing points that can directly develop into new plants. Seed potatoes store large amounts of starch and nutrients, allowing young plants to obtain sufficient nutrients at the early growth stage, resulting in rapid emergence, high survival rates, and uniform growth.

In addition, propagation by seed potatoes helps maintain stable varietal traits, so the new plants are consistent with the parent plant in shape, color, taste, and yield, which facilitates large-scale management and uniform harvesting. Although potatoes can flower and produce true seeds, seed propagation leads to great variation in offspring and requires a longer growth cycle, making it difficult to ensure commercial quality. Therefore, in both agricultural production and home gardening, using healthy, disease-free seed potatoes is the best way to achieve stable and high yields.

Preparing Seed Potatoes

Before planting potatoes, it is necessary to select healthy, disease-free, and virus-free seed potatoes. The tubers should have firm skins, not be soft or rotten. 10–20 days before planting, the seed potatoes should be pre-sprouted at a temperature of 15–20°C. Place them on a windowsill or a sheltered spot on a balcony, avoiding direct sunlight. When sprouting is successful, short, thick sprouts 1–2 cm long appear on the seed potatoes, with a greenish or purplish color, and they should not break easily. Potatoes smaller than a golf ball can be planted whole. If the seed potatoes are large, they should be cut into small pieces with a sterilized knife. Keep at least one eye per piece, and the cut surfaces should be air-dried for 1–2 days before planting to prevent rot.

Potatoes prefer slightly acidic soil, and a suitable soil pH is important for yield and disease control. A pH of 5.5–6.5 is ideal, as it promotes efficient nutrient absorption by the roots. Alkaline soils can lead to scab disease (rough, spotted tuber surfaces), inhibit the absorption of iron and manganese, cause leaf yellowing, and reduce tuber quality. Acidic soils inhibit root growth and can cause calcium and magnesium deficiencies, which lead to slowed potato growth and reduced yield. 1–2 weeks before planting, a small amount of lime or wood ash can be applied, but avoid heavy application during the growing season.

The soil should be loose, well-aerated, and well-drained, which is beneficial for root expansion and tuber development. Heavy, poorly drained soils can easily lead to rotting and disease. Before planting, the soil should be deep-tilled 25–30 cm, and well-rotted organic fertilizer or compost should be applied as a base fertilizer to improve soil structure. When fertilizing, avoid excessive nitrogen, which promotes leafy growth at the expense of tuber formation, and supplement with potassium as needed to encourage tuber development and enlargement.

Sowing Time

The sowing time for potatoes mainly depends on temperature and the risk of frost. Potatoes are a cool-season crop that is sensitive to high temperatures and frost, so the timing of planting has a significant impact on growth and yield. Generally, spring is the most suitable season for sowing potatoes. When the temperature stabilizes at 10–20°C and the soil has just thawed and is no longer compacted, seed potatoes can sprout smoothly, roots grow quickly, and seedlings emerge uniformly. At this time, the moderate day–night temperature difference is favorable for both above-ground stem and leaf growth and underground tuber formation.

Planting too early, when the soil is still cold, may lead to rotting seed potatoes and slow emergence, while planting too late may expose the crop to high temperatures during tuber bulking, resulting in excessive leaf growth but poor tuber development. In warmer regions, autumn sowing is also an option, avoiding the summer heat and allowing growth and harvest during the cooler autumn and winter. Therefore, avoiding high temperatures and frost and choosing a cool, stable climatic window is key to achieving high and stable potato yields.

Sowing Methods

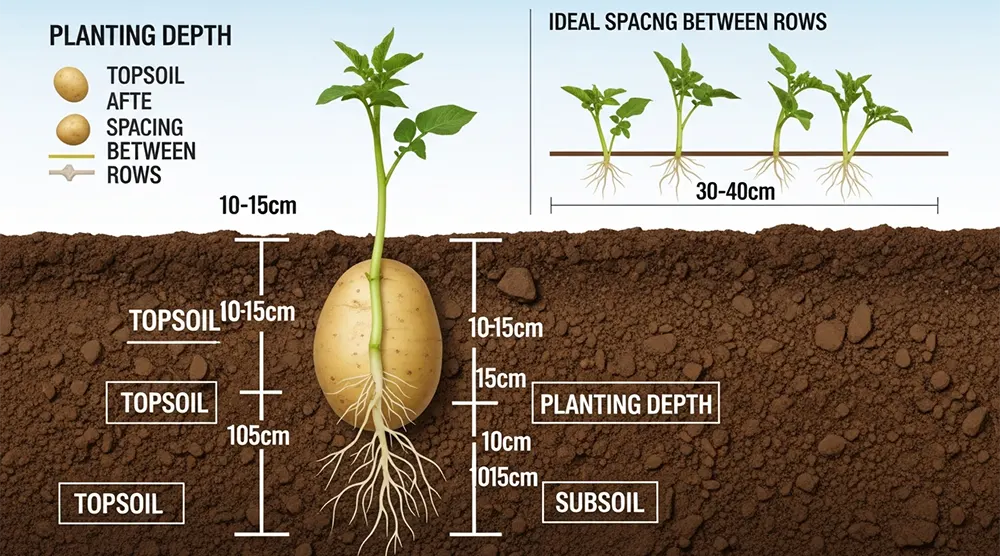

The planting density should be reasonably arranged, generally maintaining a row spacing of 30–40 cm and a plant spacing of 25–30 cm. This not only ensures that each plant receives adequate light, nutrients, and ventilation, but also provides enough space for underground tubers to expand, avoiding weak growth and small tubers caused by overcrowding. During sowing, place the seed potatoes or cut tuber pieces evenly into the furrow, ensuring that the eyes face upward, which helps the seedlings emerge along the shortest path, improving emergence speed and uniformity.

The sowing depth should be controlled at 10–15 cm. Planting too shallow can expose tubers to light during growth, turning them green and affecting edibility. Planting too deep consumes the seed potato’s stored nutrients, leading to delayed and weak emergence. After covering with soil, lightly press it to ensure full contact between the seed potato and the soil, which aids water absorption and root development.

Watering

From sowing until emergence, the seed potatoes themselves contain sufficient nutrients, so it is only necessary to keep the soil slightly moist. Excessive water can cause oxygen deficiency and rot. After the seedlings emerge, watering should be done according to soil moisture levels. The flowering stage is when the potato tubers begin to form. And the stable water supply is crucial for a good harvest. Potatoes generally require 1–2 inches of water per week, which can be obtained from rainfall or irrigation, to maintain optimal growth. Watering should be stopped when the leaves turn yellow or begin to wither. It is best to water in the early morning or late evening.

Fertilization

The nitrogen element primarily promotes the stem and leaf growth. But excessive nitrogen will lead to excessive vegetative growth, consuming a large amount of nutrients and hindering underground tuber formation, often resulting in “lots of leaves but few or no tubers.” Therefore, nitrogen should mainly be applied as a base fertilizer. During the seedling stage, you should apply small amounts of nitrogen fertilizer and avoid heavy applications in the mid-to-late growth stages.

Potassium, on the other hand, plays a decisive role in tuber formation and bulking. Adequate potassium promotes the transport of photosynthetic products to the tubers, which can increase both the number and size of tubers, and also improves dry matter content and storage quality. During the tuber formation and enlargement stages, potassium fertilizer should be the main focus, supplemented with appropriate amounts of phosphorus fertilizer, to improve yield and quality.

We recommend potassium fertilizers such as Rutom Potash Fulvate 3-0-13, an earth mineral-derived, high-potassium, water-soluble fertilizer.

Common Pests and Diseases

During potato cultivation, common problems are mainly aphids, underground pests, late blight, and scab disease, which can significantly affect both yield and quality. Aphids primarily suck the plant’s sap, causing leaf curling and stunted growth. And they are also important vectors for various viral diseases. Underground pests, such as wireworms and white grubs. They feed on tubers, creating holes and reducing market value. Among diseases, late blight can break out rapidly under cool and humid conditions, spreading quickly and causing plant death. Scab disease is often associated with alkaline soils; while it does not seriously affect edibility, it significantly impacts the tuber’s appearance.

Harvesting and Storage

Most potato varieties require about 90 to 120 days to reach maturity, although some varieties, such as Yukon Gold, can mature in just 75 days. Varieties like the russet potatoes commonly used for baking may take up to 135 days to mature. Potatoes give clear signals when they are ready to harvest. Once all tubers have formed underground, the potato plant’s leaves begin to yellow, dry out, and eventually die. Pale, papery leaves no longer perform photosynthesis or grow. You may also notice the leaves starting to fall toward the ground. When all the leaves have completely collapsed, the plant has stopped growing. Before harvesting, it is important to wait until all the leaves have fully withered.

After harvest, potatoes should be placed in a dark, cool location to allow the skins to dry, which hardens the skin and helps extend shelf life. The storage environment should be dark and well-ventilated to prevent mold and greening. The optimal temperature is 4–10°C; temperatures that are too high may cause sprouting. Before long-term storage, sort and remove any damaged or diseased tubers. Potatoes with cuts, blemishes, or disease symptoms should be consumed within the first month, as damaged tubers are difficult to store and can easily spread rot.

How to Use Potatoes

Potatoes are one of the most versatile vegetables and can be used in many ways. Potatoes can be boiled, steamed, baked, fried, or processed, making them suitable for a wide variety of dishes and dietary preferences. Common potato dishes include mashed potatoes, French fries, potato salad mixed with vegetables, eggs, or dressing, and baked or gratin potatoes with cheese or cream. Potatoes can also be processed into potato chips, dehydrated potato flakes, or potato starch.

The cooking method should be chosen based on the potato variety to achieve the best taste. High-starch potatoes (such as Russet) are ideal for frying and baking. Medium-starch potatoes (such as Yukon Gold) are suitable for mashed potatoes and gratins. Low-starch (waxy) potatoes (such as red-skinned potatoes) are best for boiling and making salads.